Fake and real. Simulacra and simulation.

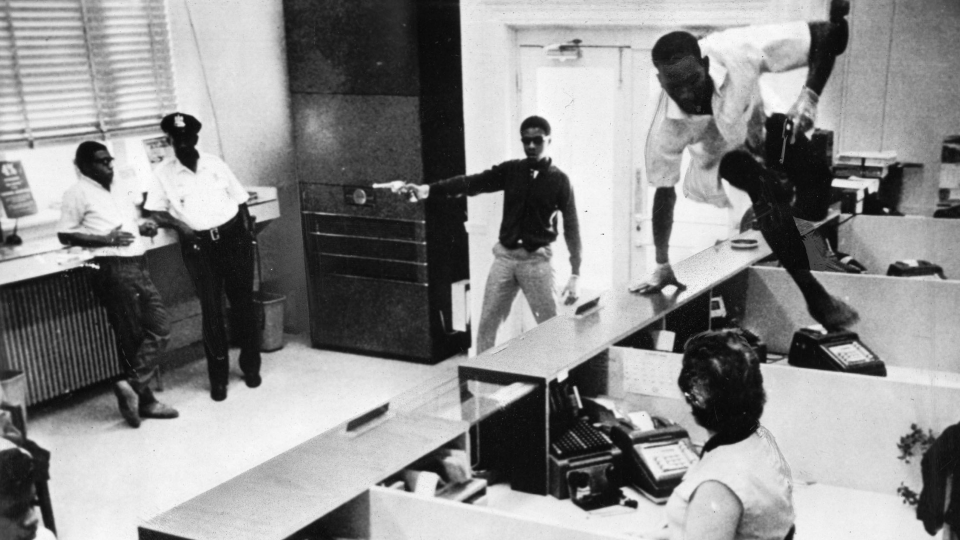

Go and organize a fake hold up. Be sure to check that your weapons are harmless, and take the most trustworthy hostage, so that no life is in danger (otherwise you risk committing an offence). Demand ransom, and arrange it so that the operation creates the greatest commotion possible. In brief, stay close to the “truth”, so as to test the reaction of the apparatus to a perfect simulation. But you won’t succeed: the web of art)ficial signs will be inextricably mixed up with real elements (a police officer will really shoot on sight; a bank customer will faint and die of a heart attack; they will really turn the phoney ransom over to you). In brief, you will unwittingly find yourself immediately in the real, one of whose functions is precisely to devour every attempt at simulation, to reduce everything to some reality: that’s exactly how the established order is, well before institutions and justice come into play.

This quote from Baudrillard’s “Simulacra and Simulation” allows us to understand very precisely simulation’s role in human society and perception.

In the media environment in which we are constantly immersed, people constantly interpret what they experience using signs, signals and clues which are real, fake, simulated, relevant, unrelated…

Going back to Baudrillard:

Thus all hold ups, hijacks and the like are now as it were simulation hold ups, in the sense that they are inscribed in advance in the decoding and orchestration rituals of the media, anticipated in their mode of presentation and possible consequences.

This observation describes what is called Hyperrealism. “More than real “. More than real because, to an extent, the “real” depends from what media show about it, from how they show it.

If I think of a holdup: although I have never really experienced one, I know how it goes, how it unfolds, how it develops. Because I have already seen it, millions of times, in movies, television, youtube videos, images. I know what to expect, what happens.

If I close my eyes, and think “bank robbery”, I will see images, hear sounds, imagine emotions, fears, excitement, the adrenaline rushes of all the participants involved: the bank robber, the police man, the hostage, the clerk.

I don’t need to actually be in a bank hold up because, through media of multiple types, I have been there a million times.

In our contemporary world, things become even more complex.

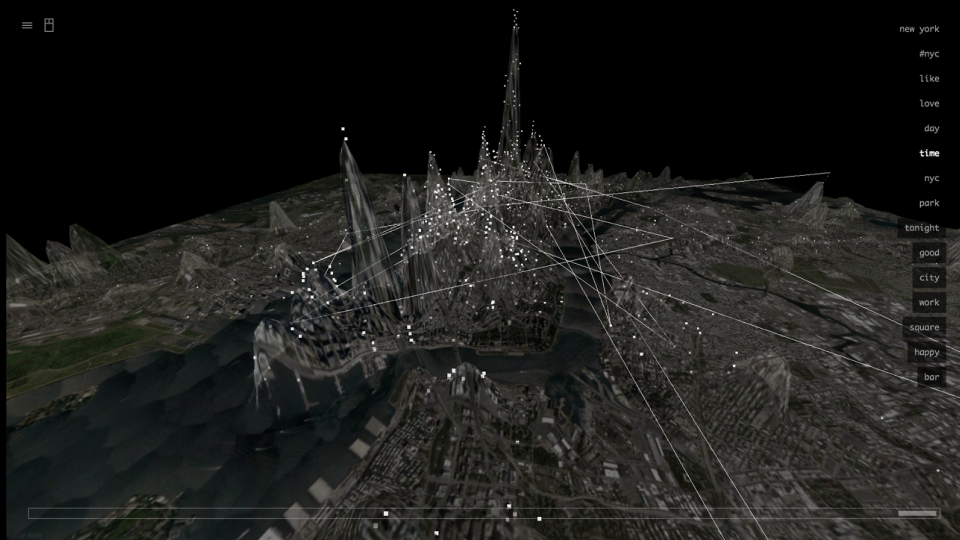

In each instant, we are constantly immersed in a multitude of flows of information and communication: the things we see, the signs and signals, the displays which we’re surrounded from, the advertisements, the things we see with the corners of our field of vision, people, their gestures, dress-codes and the ways in which we interpret them, sounds. And our smartphones.

Think about arriving in a city for the first time. You’ve never been there before. Do it.

Only a few years ago, when this happened, you really did not know much about the city: maybe you had a couple of addresses (of your hotel and a restaurant which a friend advised you to visit), you could have seen a couple of postcards or pictures, you could have read a guide… not much.

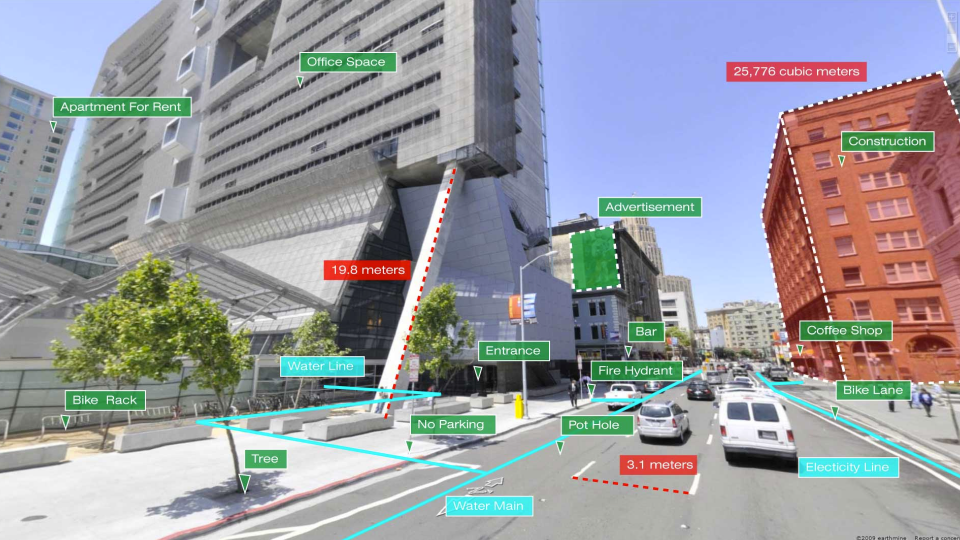

Now, everything has changed.

When you arrive in a city for the first time in your life, you have already seen it: on Google Maps, or even Streetview. You have seen pictures, read reviews, gathered opinions and experiences on TripAdvisor, asked around on Facebook, and maybe even found a few friends to meet there. You might even be couch surfing in someone’s home. Maybe you already know that a certain neighbourhood in the city is dangerous, or interesting, or full of artists, or stores.

Let’s push it: maybe you went to that city because of something you read/saw online, in the first place. Something online made you change our behaviour, or take a certain decision. If you had read something different, maybe you would have gone to a different city.

Again: you could imagine that city, have feelings for it, even without having actually been there. Simulated. And, thus, real.

That city, thus, is not only made from buildings, streets, shops, squares, houses, parks and other physical objects.

It is built from a variety of different media. Some of them very physical, like concrete, wood, glass, asphalt. Some of them immaterial, like digital information, images, videos, text, emotions, experiences, data.

All these meda entangle with each other and with our perception, forming the way in which we perceive reality.

The landscape is now composed by trees, buildings and digital information.

We can use the “traditional” senses to perceive all of them: sight, hearing, tactility, smell, taste.

Other, new, senses add up to the “traditional” ones, or modified senses, which we learned to use in more recent times. We do not have 5 (or 6) senses, but a higher number of them.

For example the sense of proprioception, which is among the senses which has undergone massive transformation in recent times: the feeling of being in a certain place. Where are we when we are non Skype, on Facebook, or while we look at Google Earth? We are in a different, other, place, which is not where our physical body is, not at our friend’s house, not on the screen, but in-between, suspended, Other.

It is necessary, in our contemporary world, to understand how to deal with this and similar facts, with this dimension.

This is fundamental for Design.

Let’s imagine designing a chair.

When I design a chair, I’m not designing an object. I’m creating a story.

A story which is the result of the entanglement multiple elements, including the chair’s shapes, materials, structural properties.

But also of a series of other elements. What do I mean when I say or imagine a “chair”? What does someone with a different culture or background mean by it? What do I expect from a chair? What do I like, hate, fear, desire from it? Which chairs have I experienced, seen, wanted, worked with in my life? …

It is an intricate story, built from formal elements, cultural ones, experiential ones, affective ones, emotional ones, and so on. Regarding me, and also all the other people which this chair is for, or who will see the chair in the store and recognise it as a chair, feel desire, attraction, repulsion, fear, love, seduction, and other emotions, feelings and meanings for it.

This is, as we were saying, even more complex in the era of ubiquitous information, in which search engines (like the image above, which is obtained by performing an image search for chairs), social networks, websites, augmented realities and more add multiple other layers to this, generated by people, companies, organisations and more.

This is not a new thing.

It has always been there: objects (and products, services, ideas, narratives…) have been stories which people interpret using their own cultures, contexts, cues and backgrounds since the beginning of mankind.

Let’s think of an incipit:

“I was alone, at sea.”

If you close your eyes, and try to visualise this incipit, what is happening in it, what do you imagine?

Different people imagine different things.

Some will think of men, women. Some will thing about homes, rafts, yachts. Some will think about sadness, or meditative states, or fear, danger, or happiness and love.

What does this mean?

It means that we create the story ourselves, in our minds.

It means that a writer (or designer, or…) never has complete control of the story, of how different people perceive it, imagine it, experience it.

It means that we build the story ourselves in our minds by harvesting a series of clues which are disseminated across a variety of media. Clues which are relevant, irrelevant, collateral, coming from what the writer wrote (or the designer designed, or developer developed, or interface designer designed…) and filtered, changed, transformed according to what we know about the world, the things we have seen and experienced. Or from what we desire, expect, envision, prefer.

Or even shaped by what we have seen online, in the streets of our city, on a billboard, or with the tail of our eye somewhere, or by something we have overheard on the bus, casually listening to what other people were saying.

All this clues, the ones we use to create the story in our heads, are disseminated across a variety of media.

Henry Jenkins defines Transmedia as:

Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience. Ideally, each medium makes it own unique contribution to the unfolding of the story.

In relation to design, we can use this definition as a starting point, to imagine Design as an act of World Building. Of creating Worlds instead of Objects.

If we do this, we would probably try to give answers to a series of “What if?” type questions.

What would be in the world if the object (product/service/application/artwork…) existed?

We know that cars exist not only for the existence of automobiles as physical objects.

We know that cars exist for a number of different reasons, possibly even more important that “cars” (as object) themselves (thing about, for example, if I don’t own a car: its other manifestations could be more important for me than the car itself in knowing about cars’ existence in the world).

Cars exist and we know it, also because we know that repair shops exist, insurance policies, parking tickets, parking lots, car advertisements, gas stations. There are people who publish pictures of their car and with their cars on social networks. There are accidents. There are people who desire certain cars. People who talk on the phone telling their friends that yesterday they ran out of gas and they had to leave the car in the middle of nowhere and walk home. There are prizes in which you win cars. There are cars lovers websites. And cars haters websites, for multiple reasons. There are car factories, and people who work in them. The same people who are on strike when the car factory in which they work shuts down because the production of cars has moved to China, or to some place else. There is the guy who invented the hydrogen car of the future. And many more manifestations of cars.

We know that cars exist because there are all of these things. And all these things exist because there are cars.

What would happen if we took away “cars” (as physical objects) and left all their other manifestations in place? With all probability, we would still think that cars exist.

In general, there are a number of transmedia manifestations of the “car” phenomenon. Which is not an “object”, but a Transmedia Narrative, a Simulacrum.

And, thus, let’s go back to the Simulacrum:

Designers (and artists, politicians, lawyers, and more and more professions) are transforming themselves, wether they realise it or not, into Transmedia Storytellers: professionals who are able to enact world-building processes by designing a Simulacrum through its coordinated manifestations across a variety of different media.

The objective of this type of actions, is twofold: to intervene on “reality” and to “loose control of the story, in controlled ways”.

First: to intervene on “reality”. On consensual reality, on the things and scenarios which we have learned to recognise as real, socially, culturally, psychologically, cognitively and more. To create a transmedia path in which the object (or product, service, law, concept, artwork…) becomes present in the world not only through its physical/digital presence, but also through the presence of its transmedia manifestations.

Not designing objects, but designing worlds.

This permits a powerful transition: to shift the perception of what is possible. By creating a World, instead of an object, we can provide the clues which allow people to believe in the possibility for this World (and for the object/service/artwork/law…) to exist.

And, second, to loose control of the story, in controlled ways.

This is, possibly, among the main opportunity for design in the Era of Knowledge, Information and Communication. The rise of Open Source, peer-to-peer production models, participatory and mutual economies and many more elements constitute evidence for this.

As described, we can use Transmedia Storytelling and World Building techniques to induce a state of Hyperreality. We can create Simulacra.

When this happens – when Hyperreality happens, when we design for Hyperreality – we do not create copies of reality, or their expansions or extensions. We create a new reality, a different one.

This allows us – as described by Deleuze – to establish a privileged position, which allows us to observe the phenomena of our world, and to open new spaces for their critical discussion.

By creating Hyperreality, we create languages and imaginaries, through the shift in perception of possibility: because we learn that something Other is possible, we acquire new language and new pieces of imagination.

And we can (and will) use them to express ourselves.

The Design becomes, thus, a platform for other people’s expression. It becomes a participatory performance.

This is of fundamental value, because through this modality people will not only able to express around their perception of possibility, but also and more importantly on the level of preferability, and of desirability. Expression not only on possible futures, but also of preferable, desirable ones.

From our point of view, this is an exceptional new role for Design and Designers.

Note: this post is the transcription of our contribution to the event on Transmedia Storytelling which was held at the MAXXI Museum in Rome.

The event is the result of the Master in Public & Exhibit Design we hold in La Sapienza University in Rome.

This year we collaborated with artist Maria Cristina Finucci on her Garbage Patch State project, by creating a complex Transmedia Narrative. Here below is the publication of the results of our work:

![[ AOS ] Art is Open Source](https://www.artisopensource.net/network/artisopensource/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/AOSLogo-01.png)