AOS will be at Frontiers of Interaction 2013 on October 24th 2013 in Milan.

At FoI2013 we will hold a workshop and a little surprise.

The workshop’s title is: “Near-future Design VS Design Fiction”

(read the second part of the article for a short discussion on what we will do)

from the FoI website:

How to make pretotypes instead of prototypes and build a transmedia narrative around them to make powerful statements about your vision for the future.

What is Design Fiction? What is Near-future Design? How can we make our vision about the future come to life? What is a pretotype, as compared to a prototype? How can Transmedia Narratives help us to turn our vision for the future into engaging, performative, ubiquitous communication? What does Baudrillard and his idea of Simulacra have to do with all this?

Who is it for: visionaries, communicators, hackers, social engineers, entrepreneurs who want to have new tools for communicating their vision about the future in the contemporary era.

Your takeaways:

-

learn about Design Fiction and Near-future Design and its tools and methodologies

-

learn how to transform your vision on the future into pretotype

-

learn how to powerfully communicate your pretotype using a Transmedia Narrative

And so, what is this all about?

“Organize a fake holdup. Verify that your weapons are harmless, and take the most trustworthy hostage, so that no human life will be in danger (or one lapses into the criminal.) Demand a ransom, and make it so that the operation creates as much commotion as possible — in short, remain close to the “truth,” in order to test the reaction of the apparatus to a perfect simulacrum. You won’t be able to do it: the network of artificial signs will become inextricably mixed up with real elements (a policeman really will fire on sight; a client of the bank will faint and die of a heart attack; one will actually pay you the phony ransom).” [p. 20]

(from Jean Beaudrillard’s “The Preecession’s of Simulacra”)

Look HERE for a nice introduction to the subject.

According to Bruce Sterling Design Fiction is:

“It’s the deliberate use of diegetic prototypes to suspend disbelief about change. That’s the best definition we’ve come up with. The important word there is diegetic. It means you’re thinking very seriously about potential objects and services and trying to get people to concentrate on those rather than entire worlds or political trends or geopolitical strategies. It’s not a kind of fiction. It’s a kind of design. It tells worlds rather than stories.”

The term diegetic prototypes (Kirby, 2010) refers to the diegesis, the fictional world, primarily, of a film within which, “…technologies exist as ‘real’ objects … that function properly and which people actually use” (Kirby, 2010:43). (in: Kirby, D. (2010) The Future is Now: Diegetic Prototypes and the Role of Popular Films in Generating Real-world Technological Development. Social Studies of Science, 40 (1), p.41-70.)

According to Kook Agency: “to produce Design Fiction means to design a campaign that is seriously possible. An object or a service that captures and focuses attention on a transformation without having to deal with global trends or geopolitical scenarios. A scenography which is able to catalyze attention and outline a possible world“. And “Design Fiction is not a type of fiction, but rather the design of our interface with reality. The culture of the project applied to the implementation of possible worlds which can only get built through stories.”

Julian Bleecker describes a slightly different point of view: “Design Fiction is making things that tell stories. It’s like science-fiction in that the stories bring into focus certain matters-of-concern, such as how life is lived, questioning how technology is used and its implications, speculating bout the course of events; all of the unique abilities of science-fiction to incite imagination-filling conversations about alternative futures.”

For example when he says

“I am interested in working through materialized thought experiments. Design fictions are propositions for new, future things done as physical instantiations rather than future project plans done through PowerPoint.”

Quoting Kirby more extensively, he clearly denotes the importance of implementing the prototype, as a tool to experience a transformation:

“..scientists and engineers can also create realistic filmic images of ‘technological possibilities’ with the intention of reducing anxiety and stimulating desire in audiences to see potential technologies become realities. For scientists and engineers, the best way to jump-start technical development is to produce a working prototype. Working prototypes, however, are time consuming, expensive and require initial funds. I argue in this essay that for technical advisors cinematic depictions of future technologies are actually ‘diegetic prototypes’ that demonstrate to large public audiences a technology’s need, benevolence, and viability. Diegetic prototypes have a major rhetorical advantage even over true prototypes: in the diegesis these technologies exist as ‘real’ objects that function properly and which people actually use.” [Kirby]

To challenge the commonplace, expected, vision of the world by materializing new objects or services within id and, thus, describing a new, augmented, world in which they exist is a very critical kind of action, that opens up the possibility to imagine, criticize and enable transformation.

As Matt Ward puts it:

Finding the uncomfortable haunting fiction that surround an object, the place where social life starts to break down and fracture is far more interesting than a world that ‘just works’.

In the same article, Matt Ward points out a series of interesting concepts. Among them:

- Fiction as a testing ground for reality

- Re-inscribing behaviour and responsibility

- in the words of Madeleine Akrich: “technical objects contain and produce a specific geography of responsibilities’”

- The decisions you make have consequences: the interesting (and often dangerous) impacts of objects happen on the outskirts of intention

All three concepts can be explored not only in terms of how the future might be, but also and more important, on the ways in which it is possible to understand how the future comes to be.

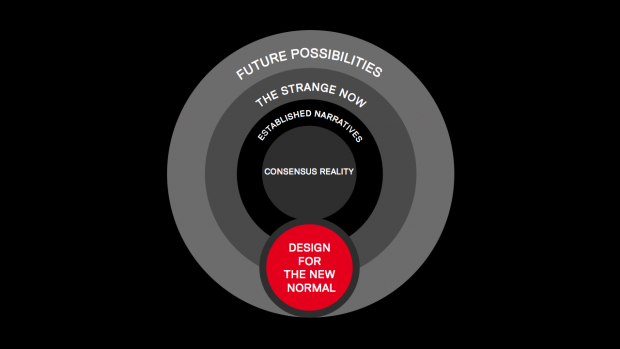

“So how do we interrupt this state hypnosis, or what Venkatesh Rao calls the Normality Field?

Design for the New Normal works to cuts through established narratives by engaging with two broad areas of interest: uncloaking the ‘strange now’, (whether that is the edge cases I showed earlier, or the disruptive forces that are hidden behind comforting metaphors); and extrapolating current trends to present the sheer breadth, of, often unsettling, future possibilities that lie ahead of us.”

and:

“These projects bypass the established narratives about the present and future that create the hypnosis of normality, and in doing so, allow for an emotional connection with the raw weirdness of our times, opening up an array of possibilities.”

Further inspection on this issue can be found in this article by Venkatesh Rao:

“Both science fiction and futurism seem to miss an important piece of how the future actually turns into the present. They fail to capture the way we don’t seem to notice when the future actually arrives.“

This brings on an interesting approach to the role of futurists,

“It turns out that the cultural edge is just as frozen in time as the mainstream. It is just frozen in a different part of the time theater, populated by people who seek more stimulation than the mainstream, and draw on imagined futures to feed their cravings rather than inform actual future-manufacturing.”

and on the idea of the (im)possibility of innovation while moving inside this domain:

“‘familiar sense of a static, continuous present’ a Manufactured Normalcy Field.”

This brings on the necessity to observe the transition. How does the “future” become the “present”?

One hypothesis is found in the same article:

“So we can divide the future into two useful pieces: things coming at us that have been integrated into the Normalcy Field, and things that have not. The integration kicks in at some level of ubiquity.”

in this distinction: “the Future Arrives via Specialization and Metaphor Expansion”.

While we observe the transition, we may come to realize that “the Milo Criterion kicks in: successful products are precisely those that do not attempt to move user experiences significantly, even if the underlying technology has shifted radically.”

While most futurists are interested in the future which is beyond the Normalcy Field, it is becoming progressively more important and interesting to the process which makes the future enter the Normalcy Field, by which it gets integrated into it, to become the New Normal.

It is interesting to borrow the terms used by John Friedman to distinguish between two sorts of conceptual metaphors we use to comprehend present reality: appreciative and instrumental. (in his book Planning in the Public Domain)

“The social validation of knowledge through mastery of the world puts the stress on manipulative knowledge. But knowledge can also serve another purpose, which is the construction of satisfying images of the world. Such knowledge, which is pursued primarily for the world view that it opens up, may be called appreciative knowledge. Contemplation and creation of symbolic forms continue to be pursued as ways of knowing about the world, but because they are not immediately useful, they are not validated socially, and are treated as merely private concerns or entertainment.”

Instrumental conceptual metaphors are basic UX metaphors like “scrolling” web pages, or the metaphor of the “keypad” on a phone.

Appreciative conceptual metaphors help us understand present realities in terms of their fundamental dynamics.

- Instrumental conceptual metaphors allow us to function.

- Appreciative ones allow us to make sense of our lives and communicate such understanding.

We do not transform the end-state conceptual models into the behavioral terms we use to actually engage and understand reality-in-use, as opposed to reality-in-contemplation. We forget to do the most important part of a futurist prediction: predicting how user experience might evolve to normalize the future-unfamiliar.

“In a way, when we ask, is there a sustainable future, we are not really asking about fossil fuels or feeding 9 billion people. We are asking can the Manufactured Normalcy Field absorb such and such changes?“

The article goes on, dealing mainly with interface design, to highlight a possible connection in this between the roles of media, technologies and narrative:

“In crafting this issue we were interested in reflecting on design fictions as a methodology and on the ways in which fictional constructs, such as future scenarios and ‘diegetic prototypes’ (D. Kirby 2009), might open design discourse. As much as we might perhaps simplistically suggest that the fictions of non-linear narrative, the achronological and asynchronous, have been central to contemporary media design and to media art, we might also say that the convergence of narrative and technology is central to design fictions: as we will see, design fictions exploit the power of media design to craft and deploy compelling visions of the future. Further than this, though, design fictions have become a significant means through which designers are exploring the ‘present’ condition of interface culture.“

This is, of course, a very interesting, significant approach, with the side effect of looping back to a technical issue (the convergence between non-linear media and narrative), instead of concentrating on the opportunities brought on by the possibility to concentrate on the idea of diegetic prototype as more than a technical expedient to explore a new interface, but as a performative act of world-building, a constructivist action of shifting the “Normal” a little further and, thus, opening up an entire set of possibilities for discussion.

Ethnographic design futurist Scott Smith suggests that one of the most compelling aspects of design fiction is the use of physical objects (and we add to this a more general connotation: concepts, be them services objects, performances … ) as entry points into a conversation about the future (as opposed to just the end-product).

This is the scenario that we will enact during the workshop:

- learn about the possibility to use methodologies coming from anthropology/ethnography/netnography to both observe the Normalcy Field and its edges, to identify “interesting” domains

- work on these domains to make sense of them, using paradox, radicalization, the boundaries of laws, ethics and common practices as our toolkit to explore implications, disruptions and transformations

- use the sense we have learned to recognize to conceptualize new “things” (objects, services, practices, actions…) and, through them, the future which they describe, the future and world in which they exist and are possible

- use transmedia narratives to build these futures as simulacra, to suspend disbelief and enable the emergence of change and interpretation.

In the process we will learn why this modality has become fundamental, in an era in which the benefits of innovation are leveraged mostly by game-changers and by the organizations and subjects who have learned how to materialize their vision on the future/present as quickly as possible in an open way which is able to suggest and evoke global discussion, by building the world in which the transformation has already happened.

![[ AOS ] Art is Open Source](https://www.artisopensource.net/network/artisopensource/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/AOSLogo-01.png)